I can think of no better match than the genre of a Bildungsroman and Herman Hesse’s focus on the experience and struggle of the individual.

In “Demian” we follow the coming of age of Emil Sinclaire from a first person perspective. At the young age of ten he discovers what he calls the “light” and the “dark” worlds. Beyond the safety, order, piety and obedience of the light world, he learns of the colorful temptations of chaos, lust and sin from the dark world.

Of the several key influential figures and events in his life, none has impacted him as much as did Max Demian, with whom Sinclaire’s fate gets magically entangled. They meet in school as young kids, where Demian confides with Sinclaire his critical remarks regarding the teacher’s teachings about the story of Abel and Cain. Demian points out how Cain is in fact not the bad person people believe him to be; that people likely made the horrific story about him up because they were afraid of him. This critical view planted a seed in the young Sinclaire: is the dark world really bad?

Sinclaire’s growing up is inextricably tangled with this core existential question: what is my fate in this life? He continues to navigates the relationship between his light and dark world, flirts with the hedonic as well as with the more pious lifestyle, all the while gratefully accepting influence from those whom he considers his private teachers, including Demian, the organ player and theologian Pistorius, and finally Demian’s mother.

What follows is what I’ve been able to make of what Sinclaire ends up believing, pretty much.

All of us must discover our fate in this life. The core teaching those who bear Cain’s sign learn is that one must act out fully that which is in oneself. What choices an individual makes, what interests one develops or job one occupies is ultimately not the important part, but only the result of what actually matters: carrying out one’s fate with full dedication. In that sense it also does not matter whether one believes in a particular god or adheres to a particular religion. One ought to discover oneself from within, and act that out.

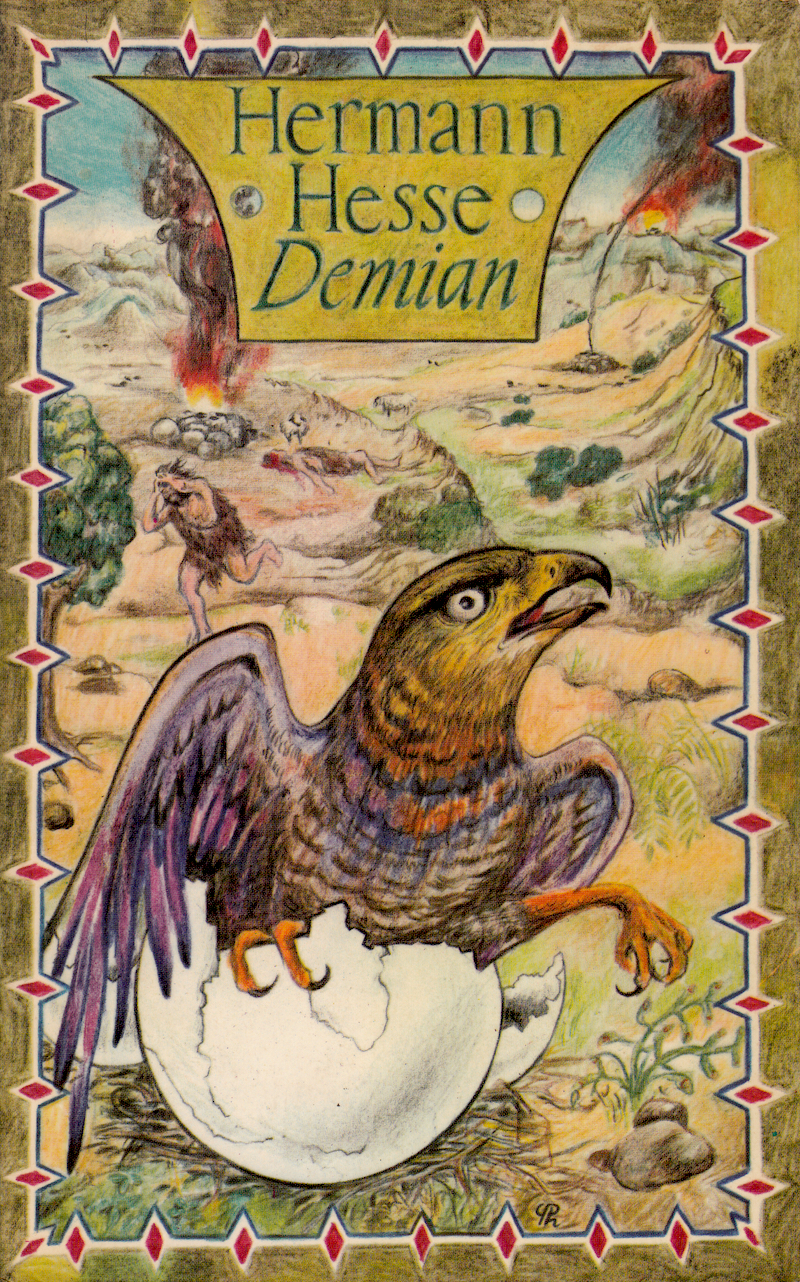

In Sinclaire’s case, his fate is to be part of the minority of people who carry Cain’s sign, who believe what mankind really is lies in the future and needs to be sought after, rather than in the present to be conserved or protected. The god he appreciates is Abraxas, who leads the new people to where the light and dark worlds are no longer opposites. To become part of this new world one needs to be reborn, so to speak, as beautifully symbolized by the sparrow who hatches from the egg that is the old world. You need to destroy a world before you can become part of the new one.

Topics such as relgiious agnosticism and particularly the lack of free will are key in the book. Attesting to the writing skills of Hesse, these topics are rarely discussed explicitly, but they are absolutely present and important. His writing is simply lovely.

It’s writers like Herman Hesse who make it possible for me, a sober atheist with as much spirituality as a mathematical theorem, to experience something aesthetic in the way I believe certain religious people do. Poetic writing that combines philosophy, spirituality and religion, and which leverages the awe inspiring raw, natural world we live in can really provide a special experience. I’m glad to have lived through another one with this great book.

Rating: ★★★★☆